October 13-14, 2012

After 16+ hours of being stuffed like a sardine in a can (but with free German beer!), I landed in Tashkent around 10pm. It took two hours to clear passport control and customs, so I didn’t arrive to my hotel until around midnight. Instead of going directly to bed, like any sane person would, I spent some time Tweeting/Facebooking/whatever and finally crashed at 2:30am.

And before I knew it, I was awake again at 6am and headed to the Fergana Valley, a five hour drive away. Uzbekistan has interesting radio stations, by the way. One minute they’ll be playing the Beatles’ “Back in the USSR” (ironic, no?) and the next minute MC Hammer’s “Too Legit to Quit”. Yes, MC Hammer.

Tashkent itself appeared to be like every other post-Soviet city I had previously traveled to, with plenty of communist block apartments, wide boulevards, and grandiose monuments. Although I didn’t see sheep grazing in the medians of Kiev and Moscow, so that was something new. But those were just cursory observations; I would return to Tashkent a few days later to explore further.

Outside the city limits of Tashkent, the scenery changed to cotton fields and herders driving their cattle along the roadside. In the small towns along the highway, old men gathered at dilapidated chaikhanas to sip tea and trade stories. Dozens of cars waited patiently at the entrances of palatial gas stations that have no gas to dispense; it reminded me of scenes from the Energy Crisis in the 1970s.

We began to climb the winding roads leading higher into the mountainous terrain. The views from up there were spectacular, interrupted only by the occasional police checkpoint and massive tunnels bored through the mountains, guarded at each end by Kevlar clad, Kalashnikov toting soldiers.

Finally through the mountains, we arrived in the Fergana Valley, the cotton and bread basket of Uzbekistan. Pull up the region on Google Maps and you’ll see an oasis of green surrounded by the dry, desert Tien-Shan and Gissar-Alai mountain ranges. On our way to Rishtan, where I was rendezvousing with my company’s tour group (oh yeah, did I mention this was a work trip?) we passed miles of cotton fields being picked by (mostly) women workers. There is no mechanical harvesting in Uzbekistan, so these women endure hours of back-breaking work to provide for their families. Driving further, we passed barren fields where dozens of large seismic trucks idled. Yes, the Chinese oil companies are here, eagerly searching for that black gold. My eyes began to sting – we traded our fresh mountain air for the dust and smoke of the valley. It smelled of burning trash and agricultural waste.

I’m embarrassed to admit that prior to this trip I had little knowledge of this region of Central Asia. Up until now, the only things I associated it with were ethnic conflict and Islamic fundamentalism. One of my grad school professors was slightly obsessed with these topics, so we spent a lot of class time covering them. Thankfully this visit would give me a chance to learn a bit more about the region.

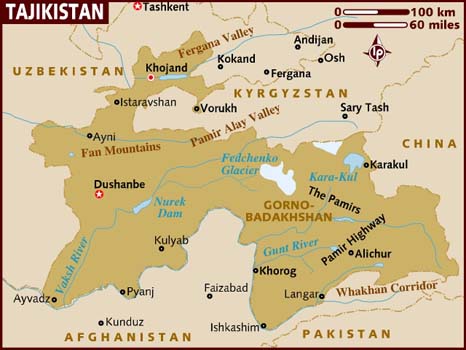

The Fergana Valley encompasses portions of three countries – Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan – but in reality the entire region is a jumble of ethnicities, rather than clearly delineated by borders. You’ve got some Uzbeks living in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, some Kyrgyz living in Uzbekistan, Tajiks in Kyrgyzstan, and well, you get the idea. The ethnic conflicts that erupted as the Soviet Union collapsed, and which continue to this day, have their origins in the 1920s, when Josef Stalin arbitrarily divided Central Asia into Soviet Republics without any regard for ethnicity.

Source: The Economist

I met up with our tour group and we headed to Kokand, a city of 192,000 that has existed since the 10th century, and, like most things in Central Asia, was razed to the ground by the Mongols in the 13th century. This would be a recurring theme of our travels throughout the region.

Here we visited the Palace of Khudáyár Khán, home of the last ruler of the Khanate of Kokand. The Khanate of Kokand was a Central Asian state that was established in 1709. But in the 1870s the Russians arrived and abolished the Khanate, declaring it part of Russian Turkestan.

Yes, finally, pictures:

Entrance to the palace

These guys asked me to take their picture, so I did.

After visiting the palace we had a few hours to rest at the hotel before dining at the home of a local family. They served the Fergana version of plov, which is the national dish of Uzbekistan and incredibly tasty. Seriously, it is one of my favorite comfort foods and I would eat it every day if I could. Lamb, rice, carrots, onions, and spices – how can you go wrong?

It was early to bed that evening, as we were departing early that morning for the portion of the Fergana Valley located in Tajikistan. Yes, I had been in Uzbekistan for barely 36 hours and was already leaving. But this trip to Tajikistan was just a quick jaunt, I’d be back in Uzbekistan the following day.

More photos here.